Class Notes 3/2/2020

Announcements: Great Decisions Lecture on Border Security on Tuesday Night and Unit Quiz #2 on Friday!

First of all, Marco started us off with Latin America in the news. He decided to look into the most recent election in Uruguay. The conservative group is now in power after 15 years of left-winged rule. This arose after many years of violence within the country, so people believe that this group will bring about change. However, the race was very close. The main reason for this topic was to enforce that there is no reason for outside intervention when it comes to other countries’ elections.

Second, we had a set up discussion about how historians should approach memoirs as primary sources for events. Historians should interrogate any source they are reading, but especially personal accounts of an event. Questions that could be asked should include:

- What kind of biases does the author have?

- Do other sources back up the events told in this memoir?

- What are the motives of the author’s work?

- How does the author depict themselves in the memoir?

- Was the memoir written during or after an event/ are the observations directly from the event or memories of the author?

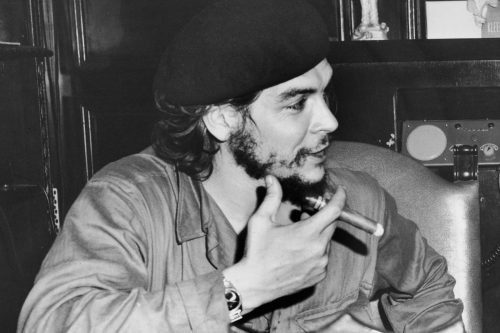

Of course, after a bit of brainstorming, we dove into The Motorcycle Diaries by Che Ernesto Guevara. Our main conversation ended up being about how Guevara became the man that he became. We started discussing whether historians can read his memoir without the interference of knowing who he becomes later in his life: a marxist revolutionary. Many decided that it was incredibly difficult to not let prior knowledge influence the way they read this, which is something to note, as we previously discussed, when reading a memoir as a primary source. One of the complexities of Che is that he was from an elite position, specifically classist, but was willing to work with lower class people in order to feel immersed into the different cultures he was experiencing. It was mentioned that Che was in a very privileged position, but tried to help out as much as he could — until he realized that the system was broken. Throughout the memoir, Che is finding his political identity through lived experiences. One of these experiences, for example, was when he attempted to help an old woman with asthma.

“I went to see an old woman with asthma, a customer at La Gioconda. The poor thing was in a pitiful state, breathing the acrid smell of concentrated sweat and dirty feet that filled her room, mixed with the dust from a couple of armchairs, the only luxury items in her house. On top of her asthma, she had a heart condition. It is at times like this, when a doctor is conscious of his complete powerlessness, that he longs for change: a change to prevent the injustice of a system in which only a month ago this poor woman was still earning her living as a waitress, wheezing and panting but facing life with dignity. In circumstances like this, individuals in poor families who can’t pay their way become surrounded by an atmosphere of barely disguised acrimony; they stop being father, mother, sister or brother and become a purely negative factor in the struggle for life and, consequently, a source of bitterness for the healthy members of the community who resent their illness as if it were a personal insult to those who have to support them. It is there, in the final moments, for people whose farthest horizon has always been tomorrow, that one comprehends the profound tragedy circumscribing the life of the proletariat the world over. In those dying eyes there is a submissive appeal for forgiveness and also, often, a desperate plea for consolation which is lost to the void, just as their body will soon be lost in the magnitude of the mystery surrounding us. How long this present order, based on an absurd idea of caste, will last is not within my means to answer, but it’s time that those who govern spent less time publicizing their own virtues and more money, much more money, funding socially useful works.

There isn’t much I can do for the sick woman” (Guevara, p. 73).

Che’s journey was one that affected him deeply, and eventually led him to becoming a revolutionary — further affecting the lives of many others.

For further reading on Che and his journey, check out these sources:

Larson, J. A., & Lizardo, O. (2007). Generations, Identities, and the Collective Memory of Che Guevara1. Sociological Forum, 22(4), 425–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00045.x https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2007.00045.x

United Nations. Statement by Mr. Che Guevara (Cuba) before the United Nations General Assembly on 11 December 1964. Accessed March 4, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bufHojkoGtw.

Reichard, Stephen. “Ideology Drives Health Care Reforms in Chile.” Journal of Public Health Policy 17, no. 1 (1996): 80-98. Accessed March 5, 2020. doi:10.2307/3342660.

With this, I close with some concluding questions:

- How does Che Ernesto Guevara’s experience represent the lives of other marxist revolutionaries?

- Was Che aware of the privilege he held while he was traveling?

- Was Che’s race an important influence in the journey that he took/ how would this experience have been different if he were not white?

Citations:

Guevara, C. (2017). The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American journey. Melbourne: Ocean.